Overview

The central objects of my research are stochastic processes on manifolds and geometric function spaces. Behind this terminology, one will find for instance constructive quantum field theory, random matrix theory or fluid mechanics, when the base space is respectively a vector space of sections, a Lie group, or a group of diffeomorphism. In this approach, I find myself using mainly tools from stochastic calculus and differential topology.

Keywords: Stochastic processes, rough path theory, Malliavin calculus, differential topology, Riemannian geometry.

List of publications

-

With I. Sauzedde, Loop soup representation of zeta-regularised determinants and equivariant Symanzik identities (2024). Abstract

We derive a stochastic representation for determinants of Laplace-type operators on vectors bundles over manifolds. Namely, inverse powers of those determinants are written as the expectation of a product of holonomies defined over Brownian loop soups. Our results hold over compact manifolds of dimension 2 or 3, in the presence of mass or a boundary. We derive a few consequences, including some regularity as a function of the operator and the conformal invariance of the zeta function on surfaces.

Our second main result is the rigorous construction of a stochastic gauge theory minimally coupling a scalar field to a prescribed random smooth gauge field, which we prove obeys the so-called Symanzik identities. Some of these results are continuous analogues of the work of A. Kassel and T. Lévy in the discrete.To appear in the Annals of Probability. arXiv:2402.00767 [link].

-

With C. Jahel, A non-de Finetti theorem for countable Euclidean spaces (2024). Abstract

The classical de Finetti Theorem classifies the probability measures on \([0,1]^{\mathbb N}\) invariant under the action of \(\operatorname{Sym}(\mathbb N)\). More precisely it states that those invariant measures are combinations of measures of the form \(\nu^{\otimes\mathbb N}\) where \(\nu\) is a measure on \([0,1]\). Recently, Jahel-Tsankov generalized this theorem showing that under conditions on some countable structure \(M\), the group \(\operatorname{Aut}(M)\) is de Finetti, i.e. \(\operatorname{Aut}(M)\)-invariant measures on \([0,1]^M\) are mixtures of measures of the form \(\nu^{\otimes M}\) where \(\nu\) is a measure on \([0,1]\). In this note, we give an example of a non-de Finetti non-Archimedean group.

arXiv:2410.22930 [link].

-

Small time expansion for a strictly hypoelliptic kernel (2023). Abstract

We consider the kernel of a hypoelliptic diffusion beyond the case of sub-ellipticity or polynomial coefficients. We get a full asymptotic expansion for small times, based on a Duhamel-type comparison with an approximate polynomial kernel. As in the sub-elliptic case, some change of scale based on the geometry of some Lie brackets yields a non-trivial limit for the kernel as time goes to zero. Remarkably, a different scale is needed to observe a non-trivial large deviation principle.

arXiv:2301.06904 [link].

-

Kinetic Dyson Brownian motion (2022). Abstract

We study the spectrum of the kinetic Brownian motion in the space of d×d Hermitian matrices, d≥2. We show that the eigenvalues stay distinct for all times, and that the process Λ of eigenvalues is a kinetic diffusion (i.e. the pair (Λ,∂ₜΛ) of Λ and its time derivative is Markovian) if and only if d=2. In the large scale and large time limit, we show that Λ converges to the usual (Markovian) Dyson Brownian motion under suitable normalisation, regardless of the dimension.

Electronic Communications in Probability [link]; arXiv:2101.10426 [link].

-

With J. Angst et I. Bailleul, Kinetic Brownian motion on the diffeomorphism group of a closed Riemannian manifold (published in 2025). Abstract

We define kinetic Brownian motion on the diffeomorphism group of a closed Riemannian manifold, and prove that it provides an interpolation between the hydrodynamic flow of a fluid and a Brownian-like flow.

Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, Classe di Scienze [link]; arXiv:1905.04103 [link].

-

Homogenisation for anisotropic kinetic random motions (2020). Abstract

We introduce a class of kinetic and anisotropic random motions \((x_t^{\sigma},v_t^{\sigma})_{t \geq 0}\) on the unit tangent bundle \(T^1 \mathcal M\) of a general Riemannian manifold \((\mathcal M,g)\), where \(\sigma\) is a positive parameter quantifying the amount of noise affecting the dynamics. As the latter goes to infinity, we then show that the time rescaled process \((x_{\sigma^2 t}^{\sigma})_{t \geq 0}\) converges in law to an explicit anisotropic Brownian motion on \(\mathcal M\). Our approach is essentially based on the strong mixing properties of the underlying velocity process and on rough paths techniques, allowing us to reduce the general case to its Euclidean analogue. Using these methods, we are able to recover a range of classical results.

Electronic Journal of Probability [link]; arXiv:1811.08415 [link].

Gauge theory from the point of view of Brownian loops

In our context, a gauge theory is a random pair \((\phi,\nabla)\) of a field and a connection. The physical models predict how those two objects should influence each other, however we do not have a satisfying formalism for the probability distribution. One stepping stone would be to understand the distribution of \(\phi\) conditionally to \(\nabla\), a direction considered by many authors. Our aim is to rewrite some of the physical observables associated to the conditioned distribution in terms of holonomies of loops, in such a way that the dependence on \(\nabla\) becomes tractable.

[Slides] The slides from a talk given in Eindhoven in September 2024.

Differential topology of dynamical random fields

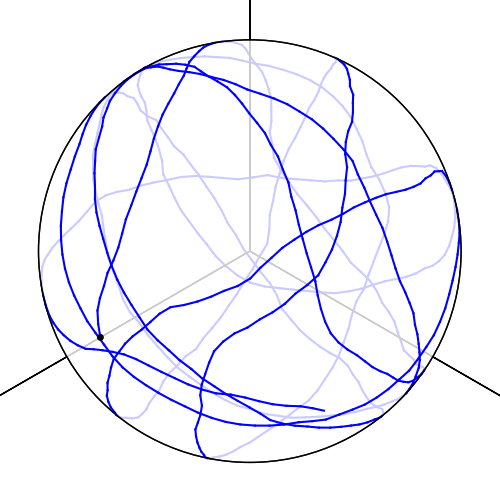

For the purpose of this paragraph, a dynamical random field is a time-dependent map \(f:(t,x)\mapsto f_t(x)\) on some smooth base space \(M\) that behaves smoothly as a function of \(x\), but can be much more chaotic, say Brownian, with respect to \(t\). To this field, we can associate geometric objects; for instance, if \(f\) takes values in \(\mathbb R^k\), then the zero set of \(x\mapsto f_t(x)\) is most often a smooth submanifold of codimension \(k\). However, under reasonable conditions, one can show that there exists a set of exceptional times \(t\) where this set is singular, and we can describe its local geometry. Similar results hold for other geometric objects, for instance the image of a map from the circle to \(\mathbb R^3\) (a dynamical knot).

[Slides] The slides from a talk given in Nancy in September 2024.